Pedestrian bridges are generally more delicate, lighter, and can have more diverse forms compared to highway bridges designed for heavy vehicles. Due to these characteristics, they require many additional calculations and checks that are not needed during the design phase of other structures.

As with any structure, a bridge must first be able to support its own weight. Once the construction is completed, all elements—such as piers, deck, cables, etc.—work together, making load-bearing relatively easier. However, during construction, load-bearing elements are subjected to loads differently from their final state and usually without the assistance of other components. Temporary support elements may be needed.

For instance, when a main beam is first placed, it behaves as a simply supported beam. Later, when combined with other beams, it acts as a continuous beam. Eventually, after a reinforced concrete deck is constructed on top, it behaves as a composite beam. In each case, the beam experiences different stresses and deformations, which can be more challenging than in its final state. Temporary construction loads also contribute to these additional stresses.

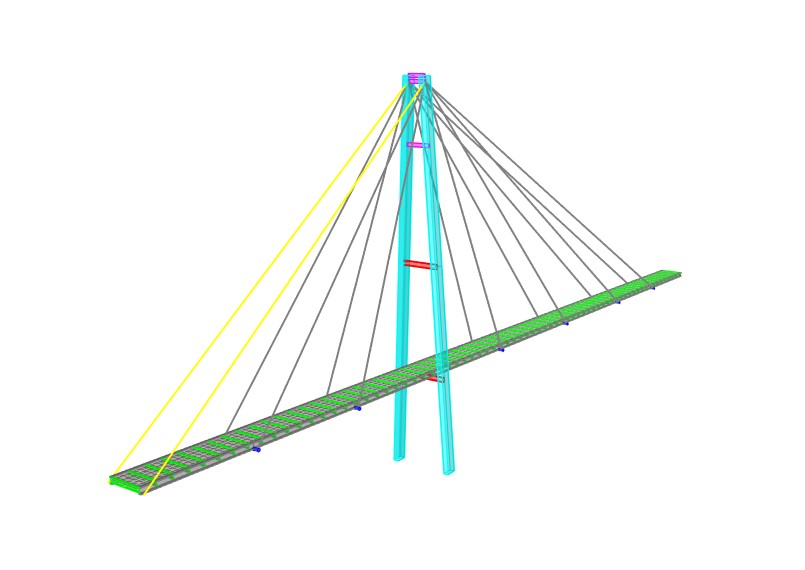

Since inclined cable-stayed steel bridges are hyperstatic systems, a force in one cable affects all the other cables. The deformation behavior of cables is nonlinear, and their stiffness varies with stress levels. Tensioning a cable changes the structure’s geometry, while the structure’s geometry, in turn, affects the tension in the cable. Therefore, the order, stage, and amount of tensioning in cables, as well as monitoring the bridge geometry throughout the construction phase, are crucial. Synchronizing the computer model with the on-site construction and making adjustments when necessary are essential for the bridge’s final strength and geometry. Consequently, the accurate construction of the bridge in the computer model before on-site implementation is crucial for the success of the project.

After the construction phase is completed, the bridge is opened to pedestrian traffic. Especially for special bridges, the opening day is of great significance. The bridge may experience the highest moving load on its opening day.

For example, when the Millennium Bridge in London was opened in 2000, about 90,000 people crossed it on the first day. Once the crowd reached a critical density, the horizontal vibration mode of the bridge synchronized with the horizontal movement of the pedestrians, leading to large amplitude lateral oscillations. People struggled to stand by holding onto the handrails. The bridge was closed two days later and reopened after about two years of testing, research, and the installation of additional dampers. Following this incident, the effects of pedestrian-induced vibrations began to be considered in the design of pedestrian bridges.

Vertical vibrations, on the other hand, have long been a limit state considered in bridge design. Vibrations caused by the similarity between the natural frequency of long-span, narrow, low-mass pedestrian bridges and the walking frequency of pedestrians can cause discomfort if they exceed certain comfort limits. Pedestrian loads, like many other human-induced actions, are both simple and complex. Although the static component resembles other moving loads, the dynamic component is influenced by several factors such as walking speed, group size, weight, footwear, step length, and more, which alter the load’s frequency and amplitude.

This complexity has led to the development of various dynamic pedestrian load models, defined differently in different codes. Since comfort limits vary from person to person, different codes have different limit values.

When it comes to wind loads and bridges, most engineers recall the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. Its engineer, Leon Moisseiff, was an innovative and bold professional. He designed the longest and most flexible bridge of his time, with a main span of 853 meters and main girders of only 2.4 meters in height. Opened in 1940, the bridge collapsed a few months later under relatively low wind speeds of 68 km/h due to excessive oscillations. Although no errors were found in the static calculations, Moisseiff was devastated by the collapse of his bridge and passed away from a heart attack a few months later. When the bridge was rebuilt, the deck girder system was replaced with a truss system, and the truss height was designed to be approximately 10 meters.

This disaster became a turning point in the study of bridge and wind interactions, leading to research on dynamic wind effects. Alongside developments in aerospace engineering, this research gave rise to the theory of aeroelasticity, which explores the interaction between wind and flexible structures.

According to the butterfly effect metaphor, the flap of a butterfly’s wings can eventually cause a storm elsewhere. The speed, direction, frequency, and height of air movement can only be predicted probabilistically and statistically. This has led many researchers to develop a variety of dynamic wind load models.

Eurocode 1991-1-4 is used for wind loads. Although it does not fully cover cable-stayed bridges, it provides preliminary checks for some calculations.

For example, to assume the structural factor cscd as 1, the frequency of the structure must be above 5 Hz—a condition typically unmet in long-span cable-stayed pedestrian bridges. Therefore, the determination of the structural factor according to Annex B or C is required.

Annex E provides formulas for checking aeroelastic instabilities. These formulas determine critical wind speeds that may initiate stability problems based on the structure’s relevant frequency, damping ratio, and cross-sectional properties. The stability of the structure is then checked by comparing these critical speeds with the design wind speeds for the location. In some cases, complete avoidance of stability problems, like those observed in the Tacoma Narrows disaster, is required. In other cases, more detailed calculations and wind tunnel tests are recommended, including the effects of stability issues.

Annex F contains formulas regarding the dynamic characteristics of the structure