Before the use of structural steel, civil engineers had to design structures using materials like stone and earth, which were in line with the spirit of the time, ensuring no tensile stresses were present. Between 0 and 100 AD, Roman engineers discovered the advantages of the arch form.

In this form, when stones were placed side by side, they worked purely in compression and did not separate from each other. Floodwaters could flow freely underneath the arch without damaging the bridge. As the weight on the arch increased, the compressive forces also increased, making the bridge stronger under heavier loads.

This ingenious design allowed the construction of bridges that could last for thousands of years.

One of the longest examples, built between 90-100 AD in Spain, is the Roman Bridge, which originally measured 755 meters with 62 spans. Currently, due to some spans being buried, it stands at 721 meters with 60 spans and is used by pedestrians. Since the maximum span without piers was limited to 10-15 meters, numerous piers were required within the river or valley.

In 1781, the first cast iron bridge was constructed in England in the traditional arch form because cast iron was also weak in tension. This bridge spanned about 30 meters with a self-weight of 13 tons per meter.

In 1874, the Eads Bridge over the Mississippi River was the first to use steel for a 150-meter span. The bridge’s designer and builder, James Buchanan Eads, was involved in a bridge project for the first time. Having spent his life around the Mississippi River, Eads made his fortune by salvaging valuable cargo from sunken steamships.

Since the bridge had to allow steamboats to pass underneath, and due to the wide span, the traditional arch form was chosen. To prevent instability of the arch under uneven loading, Eads introduced the idea of bracing the arch with truss elements at regular intervals, ensuring structural stability.

Over time, bridges became lighter, more slender, and capable of spanning longer distances without supports. Yet, the desire to build even lighter, slenderer, and longer bridges never ceased.

Emergence of the Network Arch

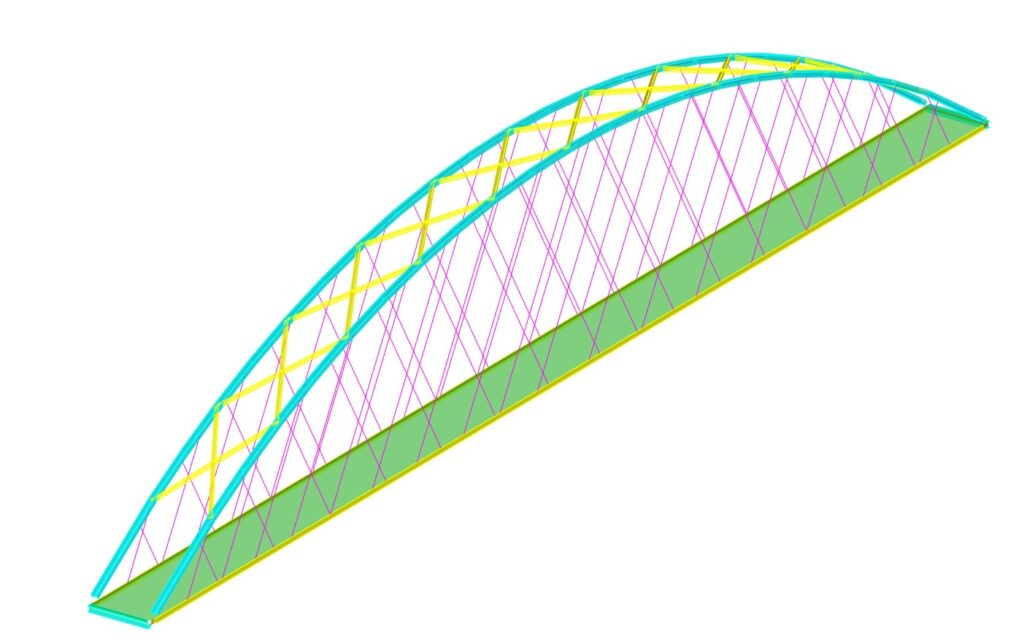

In 1955, Norwegian engineer Dr. Emeritus Per Tveit conceived the idea of the Network Arch Bridge while working on his master’s thesis. The concept involved connecting inclined or vertical steel cables or rods from the deck to the arch at regular intervals, allowing for slender deck elements and wide spans.

Tveit suggested a multi-layered truss-like system by interconnecting the cables or rods in a way that they intersected at least twice, providing additional support to the arch. His calculations showed that network arches could save over 50% of structural steel compared to conventional bridges. The design was so light and slender that he even recommended using concrete for the deck to maintain adequate rigidity and ensure the necessary tension forces in the cables.

After eight years of research, Tveit was finally given the opportunity to build his first bridge in Norway. The bridge spanned approximately 80 meters with a width of 10 meters, including walkways, and used only 60 kilograms of structural steel per square meter.

Despite its many advantages, the Network Arch Bridge design did not gain widespread acceptance for many years. Looking back, one might wonder why the first network arch bridge was ever approved for construction.

The bridge was built primarily because a municipal engineer believed in supporting innovative ideas with potential. Additionally, Professor Arne Selberg, Norway’s leading bridge expert at the time, endorsed the concept, ensuring confidence in its safety and viability. However, not everyone was convinced. The Bridge Office of the Norwegian Public Roads Administration remained skeptical about the new design approach.

This hesitation can be attributed to the unconventional design philosophy, which contrasted with traditional bridge engineering methods. The complex interaction of inclined cables, multi-layered truss-like configurations, and the reliance on highly redundant systems were all unfamiliar concepts in the 1950s. Consequently, engineers were cautious about fully trusting this innovative design until its structural behavior was better understood and validated through real-world applications.

In addition to reducing the amount of steel used in the structure, the network arch bridge has many other advantages.

Since the number of cables is significantly higher than in other bridges, the degree of hyperstaticity and consequently the level of redundancy is very high. This reduces sensitivity to situations like cable breakage or cable replacement.

Since the arch ribs work under high compression, buckling must be considered. Their buckling resistance is higher because they are restrained at many more points within the plane compared to other bridges.

Due to their lower mass compared to other bridge types, they generate less inertial forces during an earthquake.

Since the steel hanger cables can be connected to each other at intersection points against out-of-plane forces like wind, vibration problems in the cables are reduced.

For example, if the structural steel weight of an 80-meter-long network arch bridge is approximately 50-60 tons, non-concrete sections can be manufactured in suitable locations and transported as a whole to their final position, allowing construction using methods such as pushing, sliding, etc. In-situ reinforced concrete production can also be easily carried out this way.

The Brandanger Bridge, completed in 2010 with a span of 220 meters and two lanes, is one of the most slender suspension bridges. Its structural steel weight is approximately 400 tons.

Today, suspension bridges have been and continue to be constructed in 27 countries.